Caring for Caregivers

Caregiving for a loved one can be both rewarding and difficult; oftentimes its perceived benefits come at a personal cost to the caregiver. Yet, no matter how you find yourself in the role of caregiver, it seems that the psychological commitment eventually begins to wear on that individual’s well-being, affecting their health and possibly hindering their quality of life. Caregivers everywhere provide a very unique and important service to people of all ages living with an illness and/or disability. Their roles entail an array of daily tasks, such as providing personal care, getting someone dressed, assisting with feeding, helping someone to the bathroom, managing finances, and in some cases providing a significant level of medical care. Think about all of the activities that you complete in your day-to-day life and now imagine having to help someone else complete those same needs. For some individuals, the thought of helping others is innate and often leads them toward a career in the healthcare field; becoming a nurse, occupational therapist, personal support worker among others. This type of caregiver is considered a formal caregiver, meaning these individuals get paid to assist others with activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) – click here to find out the difference. However, many caregivers simply find themselves in this role, oftentimes without a choice. This type of caregiver is considered an informal caregiver, meaning these individuals provide a great deal of assistance to family members, friends, or neighbors, without being paid to do so.

Implications:

Currently, in Canada there are 8.1 million carers, making up 28% of the country’s population (Statistics Canada, 2012), compared to our bordering neighbor which contain 43.5 million carers, encompassing 13% of the America’s population (AARP, 2015). Despite the differences, both countries face similar challenges. The demand for informal caregivers is increasing each year as society faces heightened health pressures and economic instability, including aging populations, increased incidences of cancer, chronic illnesses and disabilities, and widespread inequality; among others (Barney & Perkinson, 2016). With that being said, families today are having fewer children, further increasing the demand for informal caregivers (Roth, Perkins, Wadley, Temple, & Haley, 2009). With less help available, caregivers are sacrificing their own physical, financial, and psychosocial well-being in an attempt to uphold familism and maintain well-bonding relationships.

“Evidence shows that most caregivers are ill-prepared for their role and provide care with little or no support, yet more than one-third of caregivers continue to provide intense care to others while suffering from poor health themselves.” (Navaie-Waliser, et al., 2002).

Caregivers must also make the difficult decision as to whether they will be able to maintain a part-time or full-time job while caring for their loved one(s). The stress associated with trying to keep everything afloat can actually affect a person’s immune system for up to 3 years after their caregiving ends, thereby increasing the caregiver’s chances of developing a chronic illness, or experiencing symptoms of depression or anxiety (Glaser & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2005). Additionally, older adult spousal caregivers with a history of chronic illness and susceptible to heightened stress have a 63% higher mortality rate than their noncaregiving peers (Schulz, & Sherwood, 2010).

Personal Barriers

While caring for someone you love, you may begin to find yourself falling into a routine that stands in the way of caring for yourself. Even after you wean out of your role as a caregiver, it is difficult to start putting your health and wellbeing first. Identifying personal barriers and breaking old habits is not an easy task, but it can be done—regardless of your age or situation. Further to the point, prioritizing your health and wellbeing will not only improve your own occupational engagement but it will also allow you to feel better equipped as a caregiver. Ask yourself the following questions.

Do you feel like you struggle with:

Finding time for yourself?

Balancing work and family responsibilities?

Managing your own emotional and physical stress?

Keeping the person you care for safe and being able to manage their behaviors?

Knowing how to talk with health care professionals about your loved one, as well as, yourself?Finding appropriate resources to help supplement your knowledge?

Making end-of-life-decisions?

Do you feel like your efforts go largely unnoticed?

Do you feel isolated, burnout and/or exhaustion?

Do you place unreasonable demands on yourself as a caregiver?

How to move forward?

If you’ve answered yes to ANY of the above questions, you are not alone. Caregivers often get little time to themselves, with very few breaks. Every moment of their day is occupied in some kind of work – whether full or part time in addition to caregiving duties. The combination of prolonged stress and the physical demands of caregiving can significantly affect one’s health and wellness. Although there are subliminal policies in place to support caregivers at their workplace, there are a few big organizations, such as the International Alliance of Carer Organizations (IACO) and Family Caregiver Alliance (FCA) making a massive footprint on behalf of informal caregivers. For example, the International Alliance of Carer Organizations is a global entity that provides cohesive direction, facilitates information sharing, and actively advocates for carers on an international level. They support and recognize unpaid carers by focusing their efforts on empowering them to improve their health and well-being, as well as bring about a greater balance to their lives. Additionally, the Family Caregiver Alliance seeks to improve carers quality of life through education, services, research and advocacy. Both organizations offer information on current social, public policy and caregiving issues, as well as provides assistance in the development of public and private programs for caregivers.

Taking Responsibility for Your Own Care

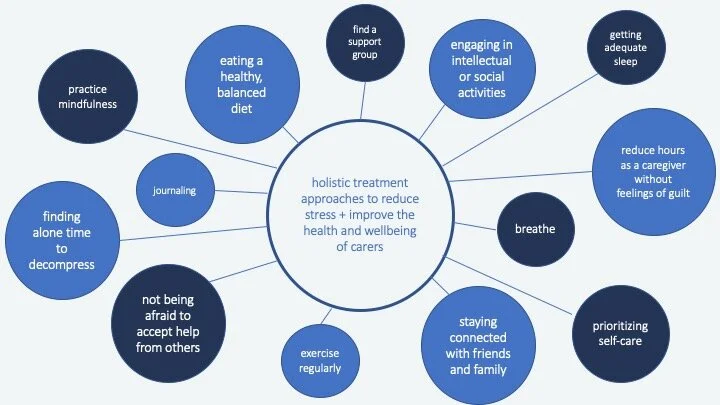

In the following mind-map you will find some beneficial treatment approaches that you can tailor to your own personal identity. These approaches aim to reduce stress, enhance occupational engagement, prioritize self-care, and act as a starting point to improving your health and wellness. Additionally, many of these approaches will address body functions and structures and act to enhance participation in activities you enjoy. As always, make sure to communicate with a physician if you’re feeling burnout, isolated, depressed, and/or anxious.

Lastly, do not be afraid to mention your personal thoughts and feelings to your loved one’s health care professional team. They are there for you as much as they are there for your loved one. I hope this resource has validated your role as a caregiver, has recognized some of your concerns, and has reignited your light to care not only for others, but for your own being.

Cassandra

Resources:

Barney, K., & Perkinson, M. (2016). Occupational Therapy with Aging Adults. Elsevier: ISBN 9780323067768

Byrne, K., & Orange, J. B. (2005). Conceptualizing communication enhancement in dementia for family caregivers using the WHO-ICF framework. Advances in Speech Language Pathology, 7(4), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/14417040500337062

Glaser, R., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. (2005). Stress induced dysfunction: Implications for health. Nature Review Immunology, 5(3), 243–251. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15738954/

International Alliance of Carer Organizations. (2018). Global State of Care [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://internationalcarers.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/IACO-EC-GSoC-Report-FINAL-10-20-18-.pdf

Navaie-Waliser, M., Feldman, P. H., Gould, D. A., Levine, C., Kuerbis, A. N., & Donelan, K. (2002). When the caregiver needs care: the plight of vulnerable caregivers. American journal of public health, 92(3), 409–413. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.92.3.409

Schulz, R., & Sherwood, P. R. (2010). Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Journal of Social Work Education, 44(3), 105–113. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2791523/pdf/nihms159443.pdf

Watford, P., Jewell, V., Atler, K. (2019). Addressing the Needs of Female Spousal Caregivers Through Journaling and a Time-Use Log. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(4). Retrieved from https://ajot.aota.org/article.aspx?articleid=2754906